Iran’s fascinating way to tell fortunes

Article continues below

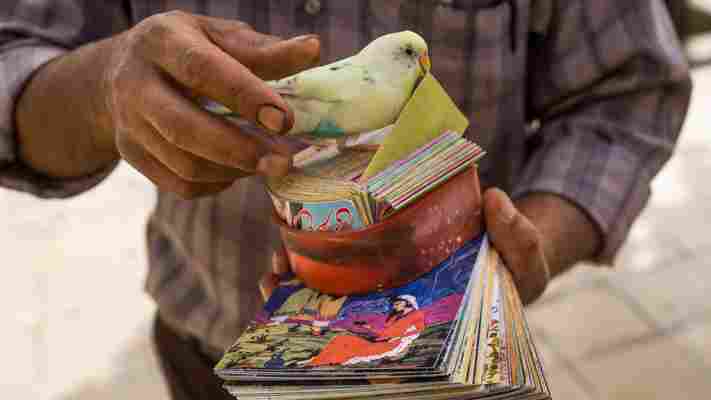

I was sauntering about the foothills of the mountains in Tehran with my friend Jamshid, and Shirin, a girl he was courting. A friend of Shirin’s had just been diagnosed with cancer, and Jamshid and I were trying to console her, insisting that everything would turn out fine – but to no avail. As we were walking towards one of my haunts for chai and ghalyan (water pipes), we came across a wizened old man with a canary perched on a little box of coloured cards.

“Wait,” Shirin told us, walking towards him while drawing money from her purse. She handed him a note, closed her eyes and clasped her hands together while the little bird hopped about and pulled out a card at random with its beak. As she read the poem written on the back, a smile broke out on her face.

“What does it say?” Jamshid asked her.

“Thank God,” Shirin replied with a sigh, reading the opening line: “‘Joseph the lost shall return to Canaan – grieve not. ’ It means she’s going to be OK.”

While in Tehran, Iran, writer Joobin Bekhrad’s acquaintance was reassured by a fortune picked at random by a bird (Credit: ERIC LAFFORGUE/Alamy)

Of love and wine

Poetry occupies a particularly hallowed space in Iranian culture. Far from merely appreciating poetry as an art form, we Iranians – of all backgrounds and socio-economic classes – live and breathe it. A street sweeper will quote Khayyám on the transience of life, just as a taxi driver will recite the mystic verse of Rumi and a politician will invoke the patriotism of Ferdowsi. On the other hand, my great-uncle, just like Voltaire, loved the instructive Sa’di to the point that he chose our family name (Bekhrad, meaning ‘wise’) from a line in one of his poems. However, when it comes to Persian belles-lettres, it is Hafez who unquestionably reigns supreme in the hearts and minds of Iranians.

You may also be interested in: • The mystics who found meaning in solar panels • The ancient Samaritans alive today • The god that gets people out of jail

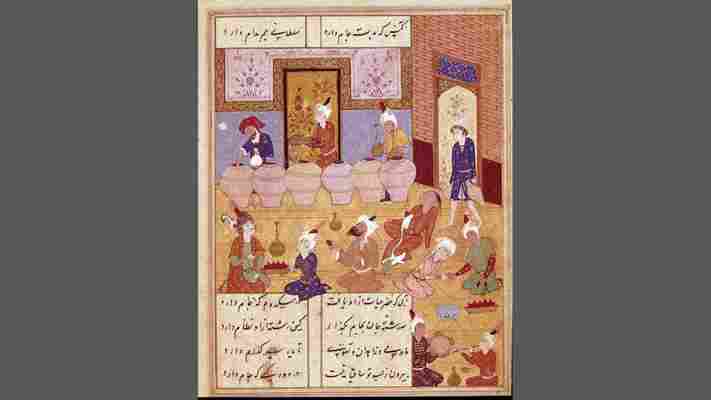

A 14th-Century poet, Hafez spent most of his life in his native Shiraz, now popularly known as the ‘City of Poets’. He is best known for his ghazals (love poems), which constitute the bulk of his compendium, Divan. In his poems, he writes chiefly of love and wine, as well as the brazen hypocrisy of holy men and religious authorities. Never one for putting up appearances, Hafez preferred to engage in what some called ‘sin’ rather than pass himself off as a paragon of virtue. Written in a florid, yet lucid and highly readable, style, the collected works of his Divan represent what many believe to be the glittering zenith of Persian poetry.

As beloved as Hafez’s poetry is, it is perhaps just as controversial as it was when it was written – a fact that might account for its immense popularity throughout the centuries. In modern-day Iran, Hafez is peerless, adored as an almost godlike figure. His poetry is often sung and set to classical Persian music. His tomb in Shiraz incessantly bustles with devotees, admirers and tourists from around the world.

Most interesting, however, is the popular Iranian tradition of using Hafez’s poems for divination; in other words, what Shirin did that day in Tehran.

The collected works of Hafez’s Divan represent what many believe to be the glittering zenith of Persian poetry (Credit: Leemage/Getty Images)

The ‘Tongue of the Unseen’

Known as fal-e Hafez (which roughly translates to ‘divination via Hafez’), the tradition involves consulting the poet – known as Lesan ol Gheyb (‘Tongue of the Unseen’) – for questions about the future, as well as guidance regarding difficult decisions and dilemmas.

The tradition of fal-e Hafez has been practised in Iran (and elsewhere in the Persian-speaking world, such as Afghanistan) for centuries. According to a well-known story, it originated upon the death of the poet. In a 1768 letter to the Orientalist Sir William Jones, the Hungarian nobleman Count Károly Reviczky, who had ‘read [the story] somewhere’, wrote that some holy men were unsure what to do with Hafez’s corpse on account of ‘the licentiousness of his poetry’. A dispute ensued as to whether or not they should bury him, after which, Reviczky writes, ‘they left the decision to a divination in use amongst them, by opening his book at random, and taking the first couplet which occurred’.

It was Hafez’s lucky day, for these were the words that were chanced upon:

From the corpse of Hafez shrink thou not; Though drowned in sin, Heaven is his lot.*

Hafez’s tomb in Shiraz, Iran, incessantly bustles with devotees, admirers and tourists from around the world (Credit: Dario Bajurin/Alamy)

Just as it’s little wonder that Hafez’s poetry is so adored amongst Iranians, so too is the custom of fal-e Hafez. Since time immemorial, Iranians have been a deeply inquisitive people, ever looking to uncover hidden meaning and mystery in the world around them. According to Columbia University’s Encyclopaedia Iranica , the Byzantine historian Agathias, for instance, wrote of Zoroastrian priests who saw the future in flames. In Iran’s national epic, the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), Ferdowsi tells (in just one of the book’s many accounts of divination) how the monarch Khosrow Parviz interpreted the accidental falling of a quince from the top of his throne as an omen of his impending death and the demise of the Sassanian dynasty. In more modern times, as Persian literature scholar Mahmoud Omidsalar writes in the Encyclopaedia, Iranians have used playing cards – and even chickpeas – to tell their fortunes; and, while some also use other books of Persian verse (such as Rumi’s Masnavi), as well as the Koran, Omidsalar posits that Hafez’s Divan is undoubtedly the most popular medium when it comes to bibliomancy in Iran.

Fal-e Hafez can be done anywhere, as long as the Divan is at hand

Today, you can have your fortune told by the bard of Shiraz just about anywhere in Iran. Men with trained birds proffer their cards of poetry on busy streets as well as at popular recreational spots for locals and tourists, such as Darband in Tehran where Shirin had hers told, and Hafez’s tomb in Shiraz. In major cities like Tehran, which are notorious for their often near-stagnant traffic, children (sans the gimmicky birds) gather at bustling intersections to do the rounds at lengthy red lights, letting curious passengers pick out poetry cards at random to (hopefully) set their hearts at ease.

While vendors of Hafez poem-cards abound throughout Iran, fal-e Hafez can be done anywhere, as long as the Divan is at hand. Just think of a question (never to be divulged to anyone) and turn to a page in the book at random for the response. Should I take that trip to Venice? Is my lover cheating on me? Will I get the job? As says the proverb, only God and Hafez of Shiraz know the answer – which will chiefly lie in the first couplet that one sees. Iranians consult the poet any time they so desire, although major Iranian festivities marking turning points – such as Norooz (the Iranian New Year) and Shab-e Yalda (the Winter Solstice) – are particularly popular occasions.

The practice of fal-e Hafez involves consulting Hafez for questions about the future and guidance regarding difficult decisions (Credit: Tina Manley/Alamy)

Shirin was fortunate to receive a positive response from Hafez, who doesn’t always have good news in store. That same year, I, too, closed my eyes, asked a question in my mind and reverently opened the Divan at random. Iran was to play Argentina the following day in the 2014 World Cup, and I wanted to know if our boys would send Lionel Messi off the field with his tail between his legs. It was with much dismay that my eyes fell on the following lines:

For this age’s sorrows, to which no end I see, Save purple wine, I know no other remedy.*

As I soon found out, it wasn’t only wine that Hafez knew a thing or two about, but the World Cup, too. As sure as he’d put it, it was Messi who sent us packing, and not the other way around.

A poet for all seasons

I have Sa’di as my namesake and Khayyám as my hero – but it is with Hafez that I, like the overwhelming majority of my compatriots, live. As a child, I could never understand my paternal grandmother’s fascination with Hafez, or why my maternal grandfather used to quote the poet day and night, and keep a threadbare copy of his Divan on his living-room table, like some sort of permanent fixture (it’s still there).

Today, you can have your fortune told by the bard of Shiraz just about anywhere in Iran (Credit: John Moore/Getty Images)

Least of all could I appreciate how, on Shab-e Yalda, my aunt would close her eyes, whisper something to herself, and open that same threadbare Divan to see what ‘dissolute old Hafez’ (as Friedrich Engels once described the poet in a letter to Karl Marx) had to say in response to her questions.

With time, I have come not only to obsess over the beauty of Hafez’s poetry and consider him a kindred spirit, but also to develop a penchant for fal-e Hafez. I don’t believe in fate or predestination, and in no way vouch for the efficacy of the poet as an all-round problem solver. Yet, in true Iranian spirit, I constantly find myself turning to him whenever I have a burning question or need advice on a sensitive issue.

Sure, it was quite a downer when Hafez told me Iran wouldn’t beat Argentina; but there’s an indescribable joy and comfort I feel when the poet assures (and sometimes, reassures) me that everything’s going to be OK. And isn’t that what we all, Iranian or otherwise, want to know – or at least believe?

*All translations are by the author

EDITOR'S NOTE: A previous version of this story included a photo caption that implied that the bird pictured in the lead image is a canary. It is a budgerigar. The caption has been amended.

The Customs That Bind Us is a series from BBC Travel that celebrates cultures around the world through the exploration of their distinctive traditions.

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter and Instagram .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Write a Comment